In the early 90s, more than two decades since its last World Cup championship title, Brazil hungered for the trophy more than any other country on earth. Yet the scars from its 1950 campaign were still not totally erased. Dubbed as the saddest day in Brazilian soccer history, July 16 1950 was the day Brazil lost the championship to Uruguay right on their home soil, and the winner’s speech prepared for Brazil had to be scrapped.

At this point, you may be wondering what the Brazilian soccer story has to do with business. Surprisingly, the analogy can ring more bells than you think.

Brazilian soccer dilemma

Back to the 1990s, during the run-up to World Cup of 1994, coach Carlos Alberto Parreira was

determined not to let history happen again.

But, he only knew too well the magnitude of challenge faced by Brazilian National soccer team. On one hand, the cheering of endeared crowds as soccer legend Pelé and his teammates lifted the World Cup trophy in 1970 still reverberated in his head. On the other hand, the grief-stricken silence of nationwide fans as they watched Uruguay took away their dream in 1950 was hauntingly real.

Somewhere in between the past and present, coach Parreira pondered upon the Brazilian samba-inspired way of playing soccer. In a country where every schoolboy dreamed of being Pelé, arguably the best soccer player in Brazil’s history and the most well-known on earth, it was hard to tell people to play differently. Brazilian children were always taught to play soccer with flair. They were enamored with the wizardry of foot play and dribbling, of playing soccer with very nimble dexterous patches of feet. But the famous method of Pelé was not working anymore.

The dry spell of World Cup titles despite fiery displays of skills between 1971 up till the early 90s stood as a daunting reminder. What previous coaches did not realize was soccer had changed a lot on the global landscape since Brazil’s last creative zenith in 1970. As the sport became increasingly popular in Europe, people there started to practice their own soccer philosophy which seemed to counteract Brazil’s individualistic and improvisational style. Germany, Italy and the Netherlands began to make their names more prominent in the World Cup finals.

Soccer was played on Astroturf by powerful players and teams who played like network of players passing the ball rapidly to each other rather than keeping it to themselves. In other words, the network structural, defensive and strength-based style of European soccer had trounced the individual Brazilian wizardry.

The champion’s comeback

Coach Parreira knew the painful time had come for a total transformation. It was not as though Brazil had never had that spark of Europe’s tactical organization before. In fact, in the very last year of Pelé’s appearance in a World Cup, Brazil did adopt a compactness-based style where the team attacked in blocks with some cohesiveness between different sectors. The job of coach Parreira then was to ignite the will to change, even if it meant starting from the root.

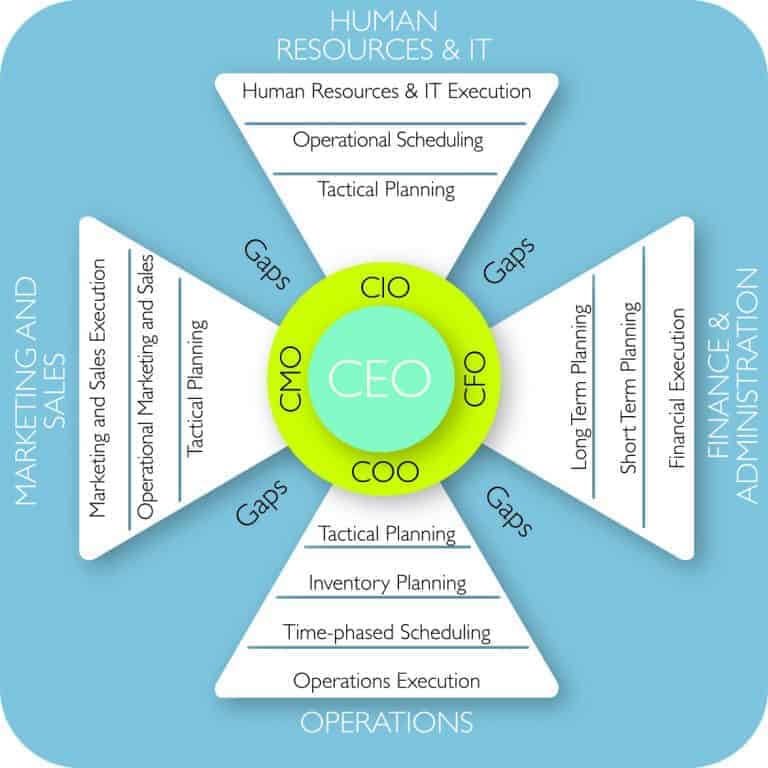

While it was not possible to change the entire soccer mentality from 5-year-old children in time for the upcoming World Cup, he determined that he would have to change the selection practices. In fact, his idea was so humongous that it was almost equal to creating a holistic large-scale business transformation that most CEOs have to do at least once every three to five years in their businesses today.

Fortunately, in 1994, Brazil made it, they won their fourth World Cup champion title. Despite being rather flat and lacking in flamboyant, spectacular footwork, the functional Brazilian unit defeated Italy and marked its successful re-assertion as a formidable team. Under coach Parreira’s guidance the team was able to learn the new model of the game, putting behind the time when it seemed the entire future of South American soccer was in doldrums.

There is a lot to learn from this transformation feat of Brazilian and South American soccer.

Their teams have moved from an individual-based game to a network of players moving together in formations, conquering the opponents by outwitting them, by outsmarting them, and by outnetworking them by using

a better method. In the next blog in this series I will talk about another national team – in another sport – which never made the transformation.

I am closely connected to that team and there is much to learn from them too – though it is not as happy story.

If you would like to read the full article in PDF format, please click

Hockey-and-Soccer-5.

In the early 90s, more than two decades since its last World Cup championship title, Brazil hungered for the trophy more than any other country on earth. Yet the scars from its 1950 campaign were still not totally erased. Dubbed as the saddest day in Brazilian soccer history, July 16 1950 was the day Brazil lost the championship to Uruguay right on their home soil, and the winner’s speech prepared for Brazil had to be scrapped.

At this point, you may be wondering what the Brazilian soccer story has to do with business. Surprisingly, the analogy can ring more bells than you think.

In the early 90s, more than two decades since its last World Cup championship title, Brazil hungered for the trophy more than any other country on earth. Yet the scars from its 1950 campaign were still not totally erased. Dubbed as the saddest day in Brazilian soccer history, July 16 1950 was the day Brazil lost the championship to Uruguay right on their home soil, and the winner’s speech prepared for Brazil had to be scrapped.

At this point, you may be wondering what the Brazilian soccer story has to do with business. Surprisingly, the analogy can ring more bells than you think.

determined not to let history happen again.

But, he only knew too well the magnitude of challenge faced by Brazilian National soccer team. On one hand, the cheering of endeared crowds as soccer legend Pelé and his teammates lifted the World Cup trophy in 1970 still reverberated in his head. On the other hand, the grief-stricken silence of nationwide fans as they watched Uruguay took away their dream in 1950 was hauntingly real.

Somewhere in between the past and present, coach Parreira pondered upon the Brazilian samba-inspired way of playing soccer. In a country where every schoolboy dreamed of being Pelé, arguably the best soccer player in Brazil’s history and the most well-known on earth, it was hard to tell people to play differently. Brazilian children were always taught to play soccer with flair. They were enamored with the wizardry of foot play and dribbling, of playing soccer with very nimble dexterous patches of feet. But the famous method of Pelé was not working anymore.

The dry spell of World Cup titles despite fiery displays of skills between 1971 up till the early 90s stood as a daunting reminder. What previous coaches did not realize was soccer had changed a lot on the global landscape since Brazil’s last creative zenith in 1970. As the sport became increasingly popular in Europe, people there started to practice their own soccer philosophy which seemed to counteract Brazil’s individualistic and improvisational style. Germany, Italy and the Netherlands began to make their names more prominent in the World Cup finals.

Soccer was played on Astroturf by powerful players and teams who played like network of players passing the ball rapidly to each other rather than keeping it to themselves. In other words, the network structural, defensive and strength-based style of European soccer had trounced the individual Brazilian wizardry.

determined not to let history happen again.

But, he only knew too well the magnitude of challenge faced by Brazilian National soccer team. On one hand, the cheering of endeared crowds as soccer legend Pelé and his teammates lifted the World Cup trophy in 1970 still reverberated in his head. On the other hand, the grief-stricken silence of nationwide fans as they watched Uruguay took away their dream in 1950 was hauntingly real.

Somewhere in between the past and present, coach Parreira pondered upon the Brazilian samba-inspired way of playing soccer. In a country where every schoolboy dreamed of being Pelé, arguably the best soccer player in Brazil’s history and the most well-known on earth, it was hard to tell people to play differently. Brazilian children were always taught to play soccer with flair. They were enamored with the wizardry of foot play and dribbling, of playing soccer with very nimble dexterous patches of feet. But the famous method of Pelé was not working anymore.

The dry spell of World Cup titles despite fiery displays of skills between 1971 up till the early 90s stood as a daunting reminder. What previous coaches did not realize was soccer had changed a lot on the global landscape since Brazil’s last creative zenith in 1970. As the sport became increasingly popular in Europe, people there started to practice their own soccer philosophy which seemed to counteract Brazil’s individualistic and improvisational style. Germany, Italy and the Netherlands began to make their names more prominent in the World Cup finals.

Soccer was played on Astroturf by powerful players and teams who played like network of players passing the ball rapidly to each other rather than keeping it to themselves. In other words, the network structural, defensive and strength-based style of European soccer had trounced the individual Brazilian wizardry.

While it was not possible to change the entire soccer mentality from 5-year-old children in time for the upcoming World Cup, he determined that he would have to change the selection practices. In fact, his idea was so humongous that it was almost equal to creating a holistic large-scale business transformation that most CEOs have to do at least once every three to five years in their businesses today.

Fortunately, in 1994, Brazil made it, they won their fourth World Cup champion title. Despite being rather flat and lacking in flamboyant, spectacular footwork, the functional Brazilian unit defeated Italy and marked its successful re-assertion as a formidable team. Under coach Parreira’s guidance the team was able to learn the new model of the game, putting behind the time when it seemed the entire future of South American soccer was in doldrums.

While it was not possible to change the entire soccer mentality from 5-year-old children in time for the upcoming World Cup, he determined that he would have to change the selection practices. In fact, his idea was so humongous that it was almost equal to creating a holistic large-scale business transformation that most CEOs have to do at least once every three to five years in their businesses today.

Fortunately, in 1994, Brazil made it, they won their fourth World Cup champion title. Despite being rather flat and lacking in flamboyant, spectacular footwork, the functional Brazilian unit defeated Italy and marked its successful re-assertion as a formidable team. Under coach Parreira’s guidance the team was able to learn the new model of the game, putting behind the time when it seemed the entire future of South American soccer was in doldrums.  There is a lot to learn from this transformation feat of Brazilian and South American soccer.

Their teams have moved from an individual-based game to a network of players moving together in formations, conquering the opponents by outwitting them, by outsmarting them, and by outnetworking them by using a better method. In the next blog in this series I will talk about another national team – in another sport – which never made the transformation.

I am closely connected to that team and there is much to learn from them too – though it is not as happy story.

If you would like to read the full article in PDF format, please click Hockey-and-Soccer-5.

There is a lot to learn from this transformation feat of Brazilian and South American soccer.

Their teams have moved from an individual-based game to a network of players moving together in formations, conquering the opponents by outwitting them, by outsmarting them, and by outnetworking them by using a better method. In the next blog in this series I will talk about another national team – in another sport – which never made the transformation.

I am closely connected to that team and there is much to learn from them too – though it is not as happy story.

If you would like to read the full article in PDF format, please click Hockey-and-Soccer-5.